The Past and Uncertain Future of the former IPS School #86

- May 25, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 30, 2022

Many may have noticed that the International School will be departing its location 49th and Boulevard this summer and will consolidate all of their operations at the Michigan Road Campus just north of the White River. Since 1998, the International School has occupied what longer term residents of Butler-Tarkington will remember as Indianapolis Public School 86.

The property where the School 86 building sits has been used for education purposes since the late 1920’s, although the site was not the original option for a school in the early Butler-Tarkington neighborhood. In August of 1928, the Indianapolis Times reported on the search for a site for the new School 86, and the possible use of a location at 52nd and Capitol. However, objections had been raised regarding this location which was being offered for sale for $29,000. The exact corner for the site is not clear, but the Times described how an engineering report detailed the flooding risk for the location, and that the site had actually been inundated during the flood of 1913. Based on this, it appears the site was the northwest corner of 52nd and Capital. The cost of filling in the site would be prohibitive, and the threat of flooding was unacceptable. While this site was passed over, debate on the site continued, with two additional competing claims being discussed in September at 49th and Boulevard and at 52nd and Illinois.

In November of 1928, the Indianapolis school board announced a proposed bond issue in order to help pay for real estate purchases adjacent to some existing schools, as well as sites for new schools. Included in this was a site for the new School 86, near Butler University. In February of 1929, the Indianapolis Star reported that the school board was negotiating for the purchase of seven lots on a plot of land on the northeast side of the intersection of 49th and Boulevard. Initially, small one-story temporary type structures were erected on the block to handle education needs for the surrounding neighborhood. These ‘portables,’ as they were called (see image below), were fairly basic, and while they were located on the same block as today’s School 86, they were moved around the property more than once.

As development of Indianapolis moved northward, and Butler-Tarkington was being platted, the Indianapolis Public Schools determined that a larger facility was needed to serve the growing neighborhood. In late 1937, Anna Torrence, the principal of School 86, appeared before the school board and requested that the board replace the existing portable buildings with a modern, permanent, structure. At the time, the portable, and its four rooms, housed 125 students, and was in a state od disrepair that the Indianapolis News reported it had become difficult to maintain temperature and handle weather conditions. Parents also complained about the deficiencies in the portable, and pushed for a more permanent solution. One parent described the portables as “ice boxes in the winter and bake ovens in the spring and fall.”

While it didn’t happen immediately, in 1939 plans for a new school were developed and the project was put out to bid. In September of that year, the school board announced the winning bids, and the general construction contract was awarded to the William P. Jungclaus Company, with a winning bid of $88,089. The building was designed by Burns & James and was of an Early American design which called for brick construction with limestone highlights. Lee Burns, one of the architects of the building, stated that “[t]he building will reflect as great a degree of charm as possible and will have as much of the pleasantness of home atmosphere as can be provided under the limitations of economy and utility.” An auditorium was planned for the western side of the building on the first floor, along with a primary room, two classroom, offices, and a clinic. The second floor would have six classrooms. The construction was completed in November of 1940, with a total cost of $230,000. The image below shows the original building as seen from the intersection of Boulevard and 49th.

This photo is dated as being taken in the 1930's, although I believe it was actually taken some time in the late 1940's. Part of this is because, as noted above, construction was not completed until 1940. Second, above the entrance in the photo is the name DeWitt S. Morgan (you have to look very closely to see it), a name which was not associated with the school until the late 1940's. In fact, in 1944, parents of students at School 86 requested that the school be named after Morgan, the recently deceased president of the Indianapolis School Board. However, Mr. Morgan had died earlier that year, and under the school board’s rules, a request to name a building after a deceased person could not be entertained until one year after the death. Below is the school board minute request from School 86's PTA regarding this request.

The engraved name stone bearing the name DeWitt S. Morgan, and the School 86 identifier, appear over the original main entrance facing 49th Street.

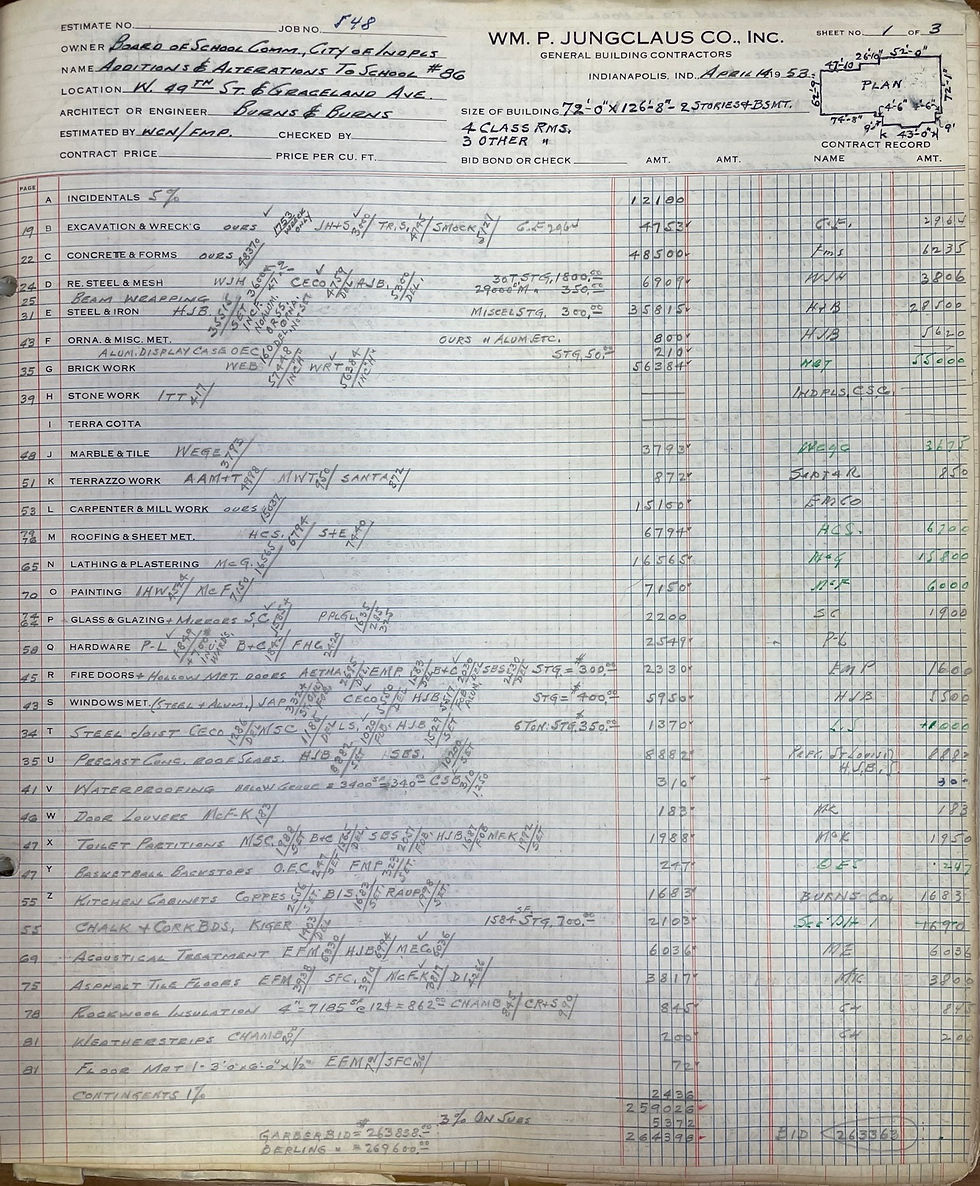

The continued expansion of the neighborhood led to School 86’s available space being maxed out 20 years later, and in 1953, the school board issued a proposal for an expansion of the School 86 building. As it had in 1939, the William P. Jungclaus Company won the bid for the project, and would construct the addition to the building the had constructed 15 years prior. The new addition was to be made on the eastside of the existing School 86 building, and included four additional classrooms, along with three other multipurpose rooms. The estimate for the addition project drafted by William P. Jungclaus Co., and contained in the archives of the successor company, Jungclaus-Campbell, can be viewed below.

The Jungclaus archives contain no images of the construction of the original School 86, or the 1953 addition. However, the Indy Digital Collections with the Indianapolis Public Library do contain images (see below) from when the addition was constructed in 1953.

These images are looking at the eastern side of the school, looking towards Butler University. Viewing the school building today, one can see the location of the addition, denoted by the seam in the roof in the middle of the structure, seen in the image below to the right of the white cupola.

The 20 years after construction were eventful for the school, characterized by high parent involvement with the school, and its connections with the surrounding neighborhood. As Butler-Tarkington became more fully integrated from south to north in the 1950’s, School 86 naturally followed suit, and its “neighborhood school” status resulted in a more diverse student body than other schools in the area. In 1968 the federal government filed a lawsuit to desegregate the Indianapolis Public School system, and on August 18. 1971, Judge Samuel Dillin, judge for the Southern District of Indiana, found that “IPS was guilty of unlawfully segregating the public schools within its boundaries.” This decision was affirmed by both the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court. However, the court also expressed doubts whether a viable desegregation plan could be established. This was because there was evidence that when a school reached a certain percentage of African American students (close 40% per the court), a "white flight" was triggered, which would result in resegregation of the school.

Judge Dillin issued an additional opinion in the segregation case on July 20, 1973 which was to establish a remedy for the segregated status of IPS. In his July 20, 1973, decision, Judge Dillin expanded upon the school percentages which would lead to resegregation, noting that around 25-30% of minority students in a school would result in the departure of white students. Dillin found that maintaining a level of integration just below the 25%-30% range, the school's integration remains stable. He noted that one elementary school in IPS, School 86, had shown this stability and was integrated:

"[I]t will be noted that there is one elementary school within IPS which has remained stable over the past five years with a high degree of integration. This lone exception is School 86, which the Court judicially knows to be located in the Butler-Tarkington area of the city, mentioned in the testimony as an area in which the residents, black and white, have worked together for the past several years in a community relation program designed to maintain the stability of the neighborhood as an integrated community. The results achieved show dramatically that such a program can be made to work, but unfortunately the other statistics illustrate all too well that the Butler-Tarkington situation is the exception and not the rule."

School 86's location in a more integrated neighborhood resulted in a higher level of diversity within its student body. Judge Dillin ultimately ordered IPS to devise a "metropolitan plan" to ensure desegregation for the district, although federal involvement in the desegregation process would continue into the 1980's. (Note: The Indianapolis desegregation case is extremely complicated and worthy of its own blog post. The brief mention here is barely scratching the surface of this massive case.)

As noted, School 86 was often recognized for its high level of parent participation in school functions and associations. In 1980, the school was recognized as one of five schools with 90% or better parent participation. In a 1983 Indianapolis Star article by Mark Nichols and Dan Carpenter, headlined “Parent power big factor in IPS disparities,” it was reported that while other schools had to go to great lengths to obtain materials for students, the principal of School 86 had to simply “stand beside her parent-teacher organization.” The location of the school, and its engaged parents provided additional resources for School 86. The Star described this as follow: “A highly supportive, mostly affluent, often demanding parent group that is willing to foot the extra costs of education had made a difference at School 86, one of the last so-called neighborhood schools in IPS.”

While School 86 was successful, it was not immune from underlying forces impacting IPS. In January of 1994, an Indianapolis Star article by Kim Hooper, reported that the strengths of School 86, might be its downfall. Under a subheading that stated “[t]he innovations and intimacy that make School 86 special may also make it extinct,” the article described 86’s ‘reasonable’ class sizes, good test scores, and parent involvement. However, School 86 fit within a profile developed by IPS principles for closure, or consolidation, of schools. 86’s building’s age, classroom space, and proximity to other schools in the system, were strikes against the school. At the time School 86 had limited space for additional students, and it was in the middle of several other schools. The continued operation of School 86 (which was smaller than some other schools) and other schools like it, were a drain on a school system looking to cut costs. Despite the cautionary tone of the Star’s article, School 86 was spared closure in 1994.

However, this was only a temporary stay, and in early 1997 IPS announced another wave of school closures, which included School 86. Ten elementary schools were to be closed, and then superintendent Esperanza Zendejas was quoted by an IPS district newsletter explaining that “[c]consolidating our resources is the best decision we can make for the children of this district.” School board president Don Payton said that “[p]robably one of the hardest jobs of an elected board member is to make these difficult decisions while being sensitive to our parents and patrons. It has not been easy for this board at all.” IPS was dealing with over 6,000 vacant seats at this time, and the schools slated for closure came from areas where the majority of the these vacancies existed. School 86 was stuck in the middle of several other IPS schools, including Schools 43, 84, and 70.

The announcement that School 86 would close ignited a firestorm in the neighborhood, with parents and students demanding the school be kept open. School 86’s status as a “neighborhood school,” and being racially balanced without the need for busing, were frequently cited reasons to keep the school open, along with its high-test scores. Supporters also cited Judge Dillen’s 1973 desegregation decision and threatened legal proceedings to halt the closure. Legal action was taken, but this, and the “fierce objections,” as described by the Indianapolis Star, raised by the supporters were unsuccessful, and the school was closed in the summer of 1997.

With the school closing, Butler University wasted little time purchasing such a large piece of property adjacent to their campus, and the transfer of School 86 building, and the lot itself, was finalized not long after its closure. Butler’s plans for the property were not clear, but the period of uncertainty following the sale to Butler ended when on December 9, 1997, it was announced that the International School would occupy the building with a five-year lease. The school had previously occupied a campus at 600 W. 42nd Street, presently the home of the Universalist Unitarian Church. That same site had previously been the home of the Orchard School. At the time School 86 was being leased, the International School had 160 students from kindergarten to sixth grade, and their use of School 86 would continue for the next almost 25 years, until the recent announcement that the International School would be leaving the School 86 building in the summer of 2022.

With the departure of the International School from School 86, a period of uncertainty, like that in 1997, returns, as questions are raised about the future reuse of the building, or whether the building will be demolished and the property redeveloped by Butler. Personally, I hope the building is retained and renovated for future educational use, perhaps with a possible modern expansion on the northside of the property.

Sources

Meeting Minutes of the Board of School Commissioners, July 1944 - December 1946, https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ips/id/195225/rec/19

Indianapolis News: September 1, 1928, December 29, 1937, October 10, 1981, March 22, 1997, December 9, 1997

Indianapolis Star: August 1, 1928, September 13, 1939, November 10, 1940, March 15, 1944, September 25, 1972, October 11, 1982, January 29, 1994, April 14, 1997, April 28, 1997

Indianapolis Times: December 29, 1937, February 1, 1939

School 86 Descriptive Data, Digital Indy, https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ips/id/410972/rec/6

IPS School News, Vol. 1, No. 7, April 1997, https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ips/id/339455/rec/1

IPS Clips, Vol. 2, No. 7., December 12, 1980. https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ips/id/335768/rec/4

Meeting Minutes of the Board of School Commissioners, July 1944 - December 1946 - Indianapolis Public Schools - The Indianapolis Public Library Digital Collections (digitalindy.org)

United States v. Bd. of Sch. Comm'rs, 368 F. Supp. 1191 (S.D. Ind. 1973)

I worked in the cafeteria at this location from 2008 to about 2015. It's a wonderful building with lots of character. It has an indoor basketball court that also serves as school theater.