eBay Find: Deposition of Thomas A. Morris

- Aug 18, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 18, 2020

As mentioned in an earlier post, I frequently search eBay looking for Indiana and Indianapolis related historical items that may have been posted to the auction site after being discovered at an estate sale or in the corner of a basement. A few years ago, while searching for Central Canal related documents, I ran across a posting for a document which claimed to be a court document related to a lawsuit involving Samuel Henderson and the state of Indiana. The eBay posting said that the subject of the lawsuit was the Central Canal, or the “ditch” as it was referred to in the document.

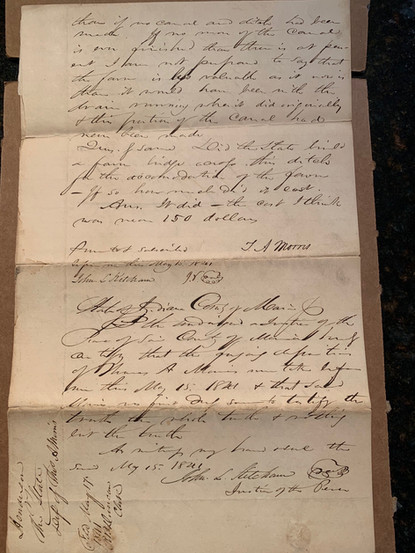

The document is two pages, with writing on both sides, and fastened together at the top, and is actually a deposition transcript. The deponent is Thomas A. Morris, an engineer who worked for the state. It isn’t clear if the deposition was in- person, or if it was what is called a deposition upon written questions, a still used discovery procedure where questions are submitted in writing to the deponent and then answered in writing in return.

The parties involved are a notable who’s who of early Indianapolis history. First, the plaintiff is Samuel Henderson, one of the city’s early European descended residents, who served as postmaster for several years in the first few decades of Indianapolis. He also ran a tavern along Washington Street, and owned large tracts of land in Marion County. Additionally, Henderson was elected as the first mayor of Indianapolis in 1847.

The deponent, Thomas A. Morris, was the son of Morris and Rachael Morris, one of the early families to call Indianapolis home. He grew up in Indianapolis, and attended West Point, graduating in 1834. Post graduation he would serve in various artillery and engineering positions within the US army. However, he only served a few years before he resigned his commission and became the engineer for the state of Indiana, where he was involved in many of the projects associated with the Internal Improvement Act of 1836, including the Central Canal and the Madison Indianapolis Railroad. In 1941, the Indianapolis Star, while discussing his military service, noted that Morris "achieved distinction as an engineer in the construction of four railroads, the Central Canal, and the famous 'state ditch' at Indianapolis...".

The attorney for the state was Hugh O’Neal, a young lawyer who had been raised in Indianapolis and who had just been admitted to the bar in 1840. He would later become Marion County prosecutor and US Attorney.

The pages appear in order as follows. Use the slider arrows to scroll through the four pages:

The handwriting on the document can be difficult to read, and many hours were spent analyzing and staring at the letters with a magnifying glass to try to transcribe the document. Websites specializing in antique handwriting were also consulted. Here is the transcription, although there may still be some errors, and there are some gaps where I could not decipher some words. If a reader spots any mistakes, or can identify the words which fill in the illegible parts, let me know via a message on the blog, or a direct message on social media.

So, what does this document tell us? First, this is just one part of a larger case. Additionally, the document could very well be incomplete, although, based on the signature lines, this might be the extent of this deposition. However, there may be other documents related to this case. While researching Mr. Henderson, I ran across two other documents from 1839 and 1840 which might be related to the document I purchased. These were located on the website www.worthpoint.com/, which tracks sales of historical documents. The document that is the subject of this post is also included on this site. The 1839 documents details what appears to be a judgment or reward of damages to Henderson and his brother in law, Henry Porter. The 1840 document is difficult to review due to the quality of the images, although I recall seeing it on eBay at the same time I first saw this Morris deposition. Unfortunately, someone else purchased the 1840 document before I could make an offer.

Additionally, the description on the eBay posting does not appear to be entirely correct. I don't believe the referenced “ditch” is the Central Canal, but is instead a separate structure, likely the “State Ditch,” a smaller drainage canal first cut in the 1830’s to help drain the swampy land north, and northeast of the city, which contributed to the flooding of the downtown area during times of heavy rain. The State Ditch remained a work in progress over the course of a few decades, constantly being modified and repaired, and drained into Fall Creek. However, the document also references the Central Canal as a separate structure, and there are questions about the viability of passing the ditch under the canal by way of a culvert.

Henderson did indeed own land which contained the ditch. John Nowland, in his 1870 work “Early Reminiscences of Indianapolis,” noted that Henderson owned and for at least a short time, lived, “on a quarter section of land a portion of which is now “Camp Morton,” or the State Fair grounds.” The map below shows the area at issue, including the State Fair Grounds along with the State Ditch which takes the appearance of a small creek running along the southern and western boundaries of the state fair grounds. (Note, this map is from 1866, and is more for illustrative purposes. As will be explained below, Henderson was no longer in possession of these lands at this time.)

A review of land patent records confirms that Henderson was the original patent owner of two 80-acre segments in section 36 of township 16. Section 36 is the smaller, highlighted square in the image below (also, note the section 36 in the map above). Additionally, he later acquired land in the adjacent west section 35, and in sections 25 and 26 to the north and west. Sections 25 and 35 included sections of the State Ditch at issue in the lawsuit. Also, sections 26 and 35 would have part of the Central Canal constructed through them (Section 35 is where the I-65 and West Street interchange is today), which may be why the canal is referenced in the deposition.

So how did this case end? I could not identify the court file for this case in the Marion Circuit Court records maintained by the Indiana Archives. There are many cases in the archives where Henderson was a party. Just not this one. However, this case is referenced by Calvin Fletcher in his diary. He noted on May 25, 1841, that the Marion County court was sitting to try Henderson’s case versus Indiana “for cutting a drain thro his land or rather diverting a ravene & throughing the water on to his tillable land.” A footnote at this point notes judgment in favor of Henderson for $900. Unfortunately, as I noted earlier, I could not find the records cited for this judgment.

A reference to this case was also found in the Indianapolis Journal on September 1, 1875. Over 30 years after the deposition, the state ditch was still causing problems. Under a headline of “Quarreling Over the State Ditch,” the Journal described the Schurman family, who owned the land north of the State Fair grounds through which the ditch flowed, had served notice on the Water Company to deepen and repair the ditch, which had been filled in and was beginning to fail. However, the Water Company claimed that any damages related to the state ditch, and the Schurman’s land, was assessed by the Marion Circuit Court in May of 1841 and “paid by the State Board of Internal Improvements on June 10, 1841 to Samuel Henderson, then owner.” Considering the above deposition took place in mid-May, this evidence, and the note in Fletcher's diary, appears to show that this case was resolved soon after the deposition by the Court.

As for the players, Henderson became the first mayor of Indianapolis after the town was incorporated as a city in 1847. He served one, two-year term, before packing up and heading west to California to join the Gold Rush (see Indianapolis Locomotive article, right). He died there in 1883. According to John Nowland, Henderson’s sale of his lands just north of downtown, referenced above, for a fraction of their cost, and his hasty departure from Indianapolis, was spurred by the advent of the railroads coming to Indianapolis. Nowland, in his Reminiscences, recounted that he ran into Henderson in “Washington City,” (unclear if he means D.C. or Washington, Indiana. I suspect the former) and that Henderson expressed concern that the railroads would ruin Indianapolis, and cause the city to retrograde, with travelers only stopping long enough to get a drink of water, thereby turning the city into a mere “waystation.”

In terms of Henderson’s land sales, it appeared that even before his term as mayor ended, he was ready to take his leave of the city. On May 22, 1848, the Indianapolis State Journal ran an advertisement for the sale of Henderson’s lands. The next year, the October 11, 1849 edition of the Indianapolis State Sentinel reported the sale of Sinking Fund lands, which included lands owned, but apparently subject to a mortgage, by Henderson, which were sold in township 16, sections 36 and 26. Section 36 is part of the original land purchased by Henderson in 1820, while the section 26 land, directly to the north, land which was referenced by the Journal above, must have been obtained at some later date. Both properties were heavily mortgaged. Perhaps this contributed to Henderson deciding to leave the city considering his financial situation. He along with many others had taken a massive financial hit during the panic of 1837, and he may not have fully recovered by the time of his departure.

T.A. Morris would continue his engineering efforts on behalf of the state, including work on the Madison Indianapolis railroad which reached Indianapolis in 1847, and the Terre Haute Indianapolis Railroad. He later made the move to railroad management, and became president of the Bellefontaine- Indianapolis railroad. He also oversaw the construction of the original Union Depot and Union Railway in Indianapolis. With the breakout of the Civil War, he served with some success in present day West Virginia. However, Morris's commanding officer, General George B. McClellan took most of the credit for those successful efforts, while on his way to being one of the most overhyped Union generals of the war. In the middle of the war Morris left military service to go back to being a railroad executive, and would later serve as one of the commissioners for the the construction of the present day state and was president of the original Indianapolis Water Company. He died in California in 1904.

References and Sources

On page two, “…in consequence of it being (illegible)…”, the word that is illegible may be “swamp.”

Eddie -- so interesting. I guess it takes young eyes to pore over these primary sources!