Faith and Litigation: The Early History of the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Indianapolis

- Aug 23, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Oct 6, 2022

This upcoming weekend (August 27) the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral (previously ‘Church’) will be hosting its 49th annual Greek Festival at the cathedral’s current location at 106th and Shelbourne Road in Carmel. The festival dates back to 1974, when the church was located on the northeast corner of Pennsylvania and 40th Street in the Meridian-Kessler Neighborhood.

The church’s history goes back to the early 1900’s, well before the start of the Greek Fest, when a small congregation began meeting in rented space at 27 S. Meridian Street in downtown Indianapolis around 1900. This was the first of four (or perhaps five) locations where the church, which was also called St. Trias, would be located over the next 120 years. Perhaps the best source for the history of the church, particularly for the early years, is a master’s thesis written by Carl Christian Cafouros, who submitted the work at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign in 1981. A link to this detailed work is in the sources and is well worth a full read. A version of the thesis was also later published as a book, and is available at the Indiana Historical Society library.

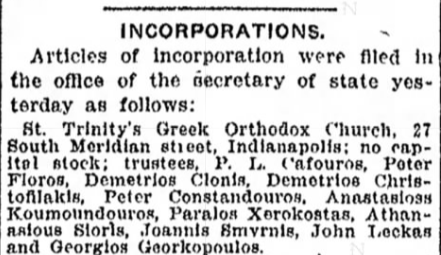

In 1903, the priest at the early church on Meridian Street left Indianapolis, and the church was on a hiatus for the next few years, until a new pastor was hired around 1905. At this time, the church continued to meet in the space at 27 S. Meridian Street. In 1910, the church, now formally known as Holy Trinity, was official incorporated under the laws of Indiana, with a board of eleven directors, and officers.

The location at Meridian Street continued to host the church until just before World War I, when a growing congregation necessitated additional space. As described by Cafouros, the church location was “inadequate” for the growing numbers of worshippers, and a potential new location was identified on West Street, opposite Military Park. At this time, the neighborhood around Military Park consisted of immigrants and families with Greek and Balkan ethnicity, along with Greek owned businesses in the area of the church, and in other parts of downtown.

An initial site, purchased by a member of the board of directors, was not used, although a two-story home at 213 North West Street, next to the first site, was purchased in 1915. The two-story wood framed house was on the east side of West Street, facing Military Park, in between Ohio and New York Streets. The site is currently occupied by the Indiana Historical Society, although a historical marker was placed at the site in 1992, and then replaced with an updated marker in 2020.

The wooden house location on West Street would serve as the church for the next five years (see photo below), until 1919 when the growing congregation, and growing industry near the church, required a move to a new building. The industry side of things came from the expansion of the Zenite Company which had operations just to the south of the church, as well as some lots their north.

As described by Cafouros, a land swap was performed between the church, the lot at 213 West Street being exchanged for a lot owned by the company at 231 West Street, just north of the church’s location, and property on New York Street. Additionally, the church was given $25,000. On this new land, and with the money obtained during the transfer, the church constructed a new, brick building at 231 N. West Street around 1920. The Baist Atlas map from 1927 shows the new brick church building at the center of the image, just north of the Zenite property. The Zenite property is where the Indiana Historical Society is located today.

Not long after this new building was completed, political issues in Greece caused turmoil within the Greek Orthodox churches stateside, including in Indianapolis. The struggle for power between two sides within the church in Indianapolis eventually led to a schism and to lawsuits and long running litigation.

Despite practicing law for 15 years, and seeing plenty of complex cases, the legal issues which arose between the two sides of the Holy Trinity Church schism are very confusing. Part of this is the underlying causes for the disagreement in the congregation, which involve post World War I Greek politics. In general terms, there was a power struggle within the Greek government, which also impacted the Greek church, and had a ripple effect across to Greek Orthodox congregations abroad. Additionally, the state courts were becoming involved in the internal operations of a church, which was a somewhat unique course of action at that time. A detailed discussion about the forces at play in this time period would cover dozens of pages and get rather far afield from the Indianapolis centric focus of this blog. However, a brief, 10,000-foot view of the situation is needed to set the stage for the internal problems facing the church in Indianapolis.

The Indianapolis media (i.e. News and Star) generally referred to the two sides as the Turk Faction and the Greek Faction. Cafouros refers to the two factions as the Royalists (who supported Constantine I, King of Greece), and the Venizelist group, who supported Eleftherios Venizelos, a Greek statesman who had led the country during World War I. Venizelos and the king did not see eye to eye, with Venizelos supporting the Allies in World War I (and being generally pro-Western) while supporting more liberal democratic viewpoints, in contrast with the monarchy, and Constantine’s desire to support the Central Powers during the war. The governing bodies for the church was split between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Patriarchate of the Holy Synod of Greece, both of which had Venizelist leanings. A Venizelist bishop, Alexander, arrived in the United States post World War I to serve as the bishop of the Greek Orthodox Church in the United States. The Holy Trinity congregation included members who supported both the royalists and Venizelists. However, after the return of Constantine I (who had been exiled at the end of the war), the Holy Synod of Greece began to shift to royalist leanings and tried to exert control over the churches in the United States, although Bishop Alexander resisted.

The two factions within the church disagreed on governance and other matters, including control of church property, and things naturally progressed towards litigation. In early 1922, the Indiana courts were called upon to decide who would control the church. On June 5, 1922, the Marion Circuit Court appointed two receivers to oversee the church, in what the Indianapolis Times called “[p]robably for the first time in the history of the State, receivers today are operating a church.” The Times also noted that the litigation was precipitated by controversy between the “royalists and democratic factions” of the church. For this part the judge acknowledged that they had probably created precedent by appointing receivers for a religious organization.

While still under the previous orders from the Circuit Court, the priest for the church, John Kargakos, and the board of trustees, acted to make the church independent from both the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Holy Synod of Greece (the latter was more in line with royalists), which exacerbated the tensions within the congregation, and isolated the Venizelists members. Disagreements between the factions at Holy Trinity continued, but with the royalists in leadership positions at the church and maintaining several seats on the board of directors/trustees, the Venizelists found themselves on the outside looking in, and increasingly left out of church functions. They sought support from Bishop Alexander who took their side and disapproved of John Kargakos as priest. However, the situation for the Venizelists remained a draw, and they eventually left the Holy Trinity congregation, and created a new church, the St. James Greek Orthodox church in early 1923. This church was originally located at 45 South West Street, but it moved to different rented locations over the next several years.

In the meantime, another lawsuit was filed on April 23, 1923, by members of the Venizelist faction in Marion County Superior Court. The lawsuit alleged violations of church law by the pastor by the royalist board of trustees n their actions to make the church independent of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Patriarchate of the Holy Synod of Greece.

On December 3, 1923, this cause went to trial. While the judge noted he was familiar with the details behind the cases through judicial knowledge (known as judicial notice today), the Times noted that the jury had to “listen to the details,” and that “[g]reat quantities of chewing tobacco have been sacrificed since trial.” and on and December 14, the jury, after a two week trial, awarded possession of the Holy Trinity to what the Indianapolis Star described as the “Turkish faction of the church congregation,” which was the Venizelist faction, and the minority in terms of church members. The Star noted that the legal dispute in the church had been pending for almost two years in various courts in Marion County.

The trial court ordered the sheriff of Marion County to put the Plaintiffs in possession of the property. However, the royalist faction was not finished. A request for a new trial was denied, but the royalist did not vacate the church property. The Venizelists attempted to oust the royalist pastor, but this effort failed when he obtained a permanent injunction in Morgan County (the case had a venue change out of Marion) in 1925 from any interference in the pastor’s employment contract.

That same year, on June 30, the Marion County Superior court appointed two receivers for the church, but in July, the royalists elected new trustees in the name of Holy Trinity, and requested the receivers be discharged, the property returned to the church, and John Kargakos, the priest at the church, be retained. One receiver, Joseph Morgan, requested that the priest be terminated, and that church property finally be turned over to the Plaintiffs in the original action which had been tried in December of 1923. The court agreed with these requests in the fall of 1925.

In March 1926 the matter was submitted to the Indiana Supreme Court for a review of the original judgment, and the various other matters which had popped up since the filing of the 1923 case. The Supreme Court’s ruling was issued on May 24, 1927. The Court found several errors by the trial court in its handling of the case, including “[i]n assuming authority without jurisdiction over the internal religious and spiritual affairs of appellant, Greek Orthodox Church, St. Trias,” and in getting involved in the contract issues between the church and Priest Kargakos. The Court reviewed the history of the litigation in a rather succinct manner (some of which was referenced above), and analyzed the errors, but ruled that the original judgment should be upheld.

In 1934, the church was reorganized and reincorporated under Indiana law, with its corporate name being “Hellenic Orthodox Church-‘The Holy Trinity’, Inc.” The Articles of Incorporation, available below for review, indicated the church was “not organized for procuring profits,” but to “maintain a public worship of Almighty God, according to the faith, cannons[sic], law, liturgy, doctrines, disciples, worship, rites, rules, usages and ecclesiastical authority of the East Greek Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church, commonly known as the Greek Orthodox Church.” Additionally, the articles note that the church would obtain property to erect a church building. The articles (available at the link below) indicate the church still had some property, which were likely the left over lots on New York, obtained from the Zenite Company.

The articles of incorporation also address how future disagreements and possible legal issues would be addressed by the church, a lesson learned from the previous 10+ years of litigation and division amongst the congregation.

The new board of directors for the church included members of both factions, and they joined together to reobtain the church property at 231 West Street, which had been lost to foreclosure a few years before. As for the disagreements between the factions, Cafouros described the pause: “A period of surface tranquility descended upon the battle-scarred community. For unity and survival, the divisive debate went into suspended animation.” Nationally, the schism within the church was resolved when the Archdiocese of North and South America was created, and the schism is Indianapolis concluded for the most part in 1934, 12 years after the initial break.

However, Cafouros notes that the “final wounds” of the schism in Indianapolis and Marion County were resolved in the 1940’s. This new church would continue to serve the congregation from the 231 West Street location for nearly 40 years, until 1959, when the church followed the path of many churches before it and moved away from the downtown core with the construction of a church at 40th and Pennsylvania.

This location continued to house the congregation for the next 40+ years, and also saw the start of the popular Greek Fest (clippings from the Indianapolis Star and News featuring the first Greek Fest below) in the fall of 1974, until 2008, when the new location in Carmel was opened. The former church building at 40th Street is currently the home to the Indianapolis Opera.

Sources

R.L. Polk & Co.'s Indianapolis City Directory, 1924

Indianapolis Star: May 12, 1922, April 1, 1922, June 6, 1922, December 15, 1923, June 30, 1925, August 17, 1974, September 29-30, 1974, January 31, 2006

Indianapolis News: May 25, 1927, September 30, 1974

Indianapolis Times: June 6, 1922, December 5, 1923

Cafouros, Carl Christian, The Community of Indianapolis: A Microcosm of the Greek Immigrant Experience (1981), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, https://hdl.handle.net/2142/104674

Members of Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church (1915), Indiana Historical Society, https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/V0002/id/2906/rec/4

Comments