Ruins on the Monon Trail: The Remains of the Maas-Neimeyer Lumberyard

- Jun 29, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 2, 2023

I’ve mentioned previously about my past bike commuting along the Monon and other routes between the near northside and downtown Indianapolis. I haven’t done this much in the past few years (thanks COVID and the closure of the Bike Hub YMCA at the City Market), but when I have recently ridden down the Monon, as discussed in this post from August of last year, I have been amazed at the amount of development along its route. Much changed from the trail in 2011.

But one landmark (at least in my own mind) has remained in place. Located at the intersection of 21st Street and the Monon Trail, on the westside of the trail, is a brick structure capped with smokestacks, and opened on its eastern side (facing the Trail).

As can be seen in the photo above, the structure is mostly overgrown with vegetation, although in the past it was much more visible. The two photos below are Google Streetview images from 2007 and 2019, as seen from 21st Street.

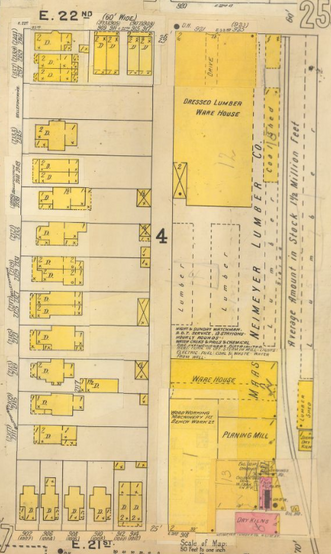

The structure is on the far southern end of the property which houses the Habitat for Humanity Restore, although its use goes back much farther, over 100 years. At that time, the land where Habitat for Humanity now sits, between 22nd and 21st street, was owned by the long defunct Maas-Neimeyer Lumber Company. The Sanborn below shows the lumberyard, side by side with what the property looks like today.

The brick structure which still stands today is identified on the Sanborn map as "dry kilns" (see close up below) and is located on the bottom right corner of the Sanborn map above. It is also visible in the aerial image. Dry kilns were essentially large ovens which were used to accelerate the drying of lumber products. The pink color of the dry kiln below means it was constructed of brick, although its eastern side was made of wood (yellow color) and was likely a large door.

The Maas-Neimeyer Lumber Company was incorporated in 1901, and at the same time purchased a large section of land along the Monon Railroad between 21st and 22nd Streets where its main operations, including planing mills, woodworking workshops, and warehouses were located. A section to the north, between 22nd and 23rd Streets, was later acquired as a lumberyard for the company. Another lumberyard occupied the block to the south of 22nd, all fronting the railroad (and present day Monon Trail). The Sanborn above is from 1898, but the maps often underwent updates and additions, and the Maas-Neimeyer complex was included in one of these additions, after the main 1898 edition was published.

The principals of the new Maas-Neimeyer Lumber Company were A.J. Neimeyer, who had been operating a company in Arkansas producing lumber from yellow pine, and George L. Maas, who had working in the lumber industry in Indianapolis for the previous few decades, and which one sources described as "an old timer in the lumber buisness." In 1902 Neimeyer sold his interest in the company to Maas, although the firm's name remained the same.

For the next two-plus decades, Maas-Neimeyer carried on its operations, and expanded its footprint at 21st and 22nd Streets. The company advertised heavily in national lumber trade journals, as well as local publications. An eBay listing for a Maas-Neimeyer price list from 1906 was found on eBay during the week of June 26th, 2023. The list includes prices for fencing, shingles, flooring, yellow pine lumber, window frames, and finishing work. Noted on the list is that the company does not list all of their products carried, so customers should call with any questions. (Note: While an interesting piece, I do not think I will be paying $75 to purchase it.)

During the years after the Maas-Neimeyer was founded the company provided lumber and finished woodworking to various local and out of state projects. One such project was the Indianapolis Athletic Association building located at the corner of New York and Meridian Street. Maas-Neimeyer provided the millwork for the project, which was designed by Robert Frost Dagget. Another out of state project was mahogany finishings for the courthouse in Memphis, Tennessee. Other local projects included the Block Building, Methodist Hosptial, L.S. Ayres Building, and the Circle Theater. An advertising brochure, available online from the Indiana State Library Trade Catalogs Collection, and published in the early 1920s, includes images of the company's various projects, including numerous homes around Indianapolis.

In 1927-28, Maas-Neimeyer underwent a merger with another lumber business, the William F. Johnson Lumber Company. The consolidation resulted in the loss of the Neimeyer name, with the new firm being called Johnson-Maas. Its operations remained at the site along the Monon Railroad.

On February 24, 1936, the Indianapolis Star featured the Johnson-Maas operation in the Indianapolis Industrial Review section of the newspaper. In this story, the. Jo-Mas Co., as the Star called it, was described as covering four city blocks with storage space and mill work operations, which included cabinet making, woodworking, and lumber processing and curing.

The Star detailed how the equipment at the company was the “most modern,” and was used to fabricate interior trim and other construction materials. The company’s treasurer was quoted by the Star as saying “[t]he size and importance of the Johnson-Maas Company is no accident. Its growth has been based on a steadfast adherence to the policies of square dealing, honest craftsmanship, basically good materials, and artistic finishing.” He continued noting that “[t]he firm is justly proud of the many fine building projects on which it has been called by architects and builders from many parts of the country.”

Despite the publicity, the firm’s long-standing operations, and the positive endorsement from its treasurer, by the late 1930s the Johnson-Maas firm began to run into financial problems, and in 1939, the company filed for bankruptcy. Newspaper ads throughout that year advertised the sale of the company’s stock and equipment. The bankruptcy continued into 1941 when the accounts receivable for the company were put up to sale by the bankruptcy estate, and the lumberyard’s operations were finally concluded.

The site of the former lumberyard underwent several uses during the years after the demise of the Johnson-Maas Company, and much of the former buildings from the lumberyard have been removed. The property was later used by an aluminum manufacturer, while the sections south of 21st were used by a “clay products” company. The area around the former Maas-Neimeyer site has also changed, with redevelopment of many of the former industrial areas into residential spaces over the past decade. The land south of 21st and fronting the Monon Trail, which used to house the company’s lumber storage areas, is now filled with new homes.

The old dry kiln building still stands today and is easily visible from the Monon Trail, although it is slowly crumbling as the years past. One of the large stacks on the building has collapsed, and hangs over the southern side of the building, facing 22nd Street. Another is leaning precariously. A smaller stack has also collapsed, although the other still stands. The wooden door on its east side is now gone, and that side is completely open, as can be seen below.

Inside the dry kiln building are two large iron cylinders, which at first glance look like boilers, although these may be the actual dry kilns referenced on the Sanborn. If you look closely, it appears that part of the ends of the of cylinders, facing the camera, can be removed, perhaps to allow lumber to be placed inside the kilns.

EDIT, July 2, 2023: I returned to this site over the July 4 weekend, and equipped with proper footwear (I wore sandals the first time I went, and there was a lot of rusted metal and glass) I explored the back end of the building more thoroughly. Some social media discussion after this blog posting was first published led me to believe that these cylinders were boilers, and I wanted to confirm this. Sure enough, I located this identifier on the far end of one of the boilers. The boilers were manufactured by Cleaver-Brooks of Milwaukee. The date November 5, 1948 is also on the identifier plate, although I'm not sure if it is the manufacture or installation date.

As discussed below, at some point the Maas-Neimeyer dry kiln building underwent a conversion to house steam boilers. Turning back to the building as it stands today, the smokestacks on the top of the kiln building exited through the roof. As noted earlier, the stacks are in various stages of collapse. The roof is generally disintegrating, likely the cause of the collapse of some of the stacks.

The west side of the building has a newer cinder block extension. It is unclear when or why this was constructed, although I suspect this was part of its conversion to steam power. That addition is pictured below. Compare this image to the images with the same vantage point included at the beginning of the post. The last Sanborn available for this property, is from the 1940's and shows the kiln building as a "warehouse." Sometime after that, likely the late 1940s as indicated by the boiler manufacturer plate shown above, the boilers were installed.

For now, the former kiln building still stands, although with the encroaching development, and the ravages of time and nature, I can’t imagine it will remain so for very many more years.

This stretch of the Monon, from 16th Street to Sutherland, used to be the home to numerous railway and industrial operations, including other lumberyards beyond the Maas-Neimeyer Company. The John M. Woolley Lumber Company, operated at the corner of 30th and the Monon from at least the middle of the 20th century, until it closed in 2016. The company had numerous dry kilns which were always in operation, and frequent riders of the Monon may remember the signs warning of vehicles crossing, since the company also owned a large lumberyard on the east side of the trail, and vehicles would be transporting lumber from the yard to the processing and drying facilities on the west side. After its closure, the property was sold in 2020, and is now the Monon 30 event space.

A still operating lumber related company, Indiana Veneers, is based just north of the former Maas-Neimeyer location along the Monon, and actually predates Maas-Niemeyer having been started in 1892. Indiana Veneers operates a mill on site which produces hardwood veneer products, using a variety of timber , including white oak, hard maple, walnut and hickory. Their website can be accessed here.

Sources

Indianapolis Star: May 29, 1921, December 30, 1922, March 4, 1928, February 24, 1936, December 9, 1939, June 3, 1941

Indianapolis News: March 4, 1901, June 23, 1939,

Indianapolis Times: July 4, 1927

Indiana (George L. Maas biographical chapter), 1919, https://archive.org/details/indiana_00chic/mode/2up

American Lumberman: The personal history and public and business achievements of ... eminent lumbermen of the United States, https://archive.org/details/americanlumberme01chicrich/page/n1/mode/2up.

The Pageant, Indianapolis Centennial, 1820-1920, https://archive.org/details/indianapoliscent00bate/mode/2up

The Architectural Forum, June 1924, Vol 40 Issue 6, https://archive.org/details/sim_architectural-forum_1924-06_40_6/mode/2up

I bike this stretch frequently and have wondered about this building. Thanks for answering that question. Another business, Indiana Veneer, must be a holdover from the Monon train days. I find it fascinating that they are still operating in this part of the city. Have you seen them watering their logs in a large lot behind their factory?